When You Can’t Get Lost in Seoul Nightlife, ‘Love in the Big City’ Is the Next Best Thing

When You Can’t Get Lost in Seoul Nightlife, ‘Love in the Big City’ Is the Next Best Thing

An exuberant hunger drives the characters of Sang Young Park’s beautiful novel

There’s a blurry photo of me, taken on one of my last nights in Seoul, taken on a city bus as it sped past blinking Gangnam lights. I’m dressed sharp — no self-respecting Korean would ever leave their apartment looking anything but — and bundled in a glossy down coat. My head tipped back, eyes closed in euphoria, I’m drinking wine straight from the bottle. I’m guzzling shamelessly in public because I’m young and I’m thirsty and I’m feeling so good from a night of feasting with friends that I don’t care what anyone thinks of me on this bus, which is nearly empty except for us, in a city that I’ve called home for nearly seven years.

Almost eight years have passed since that wild night, and as I recall it now, back here in the United States amid yet another wave of the coronavirus pandemic and potential lockdowns, I feel a desperate pang of longing for Seoul.

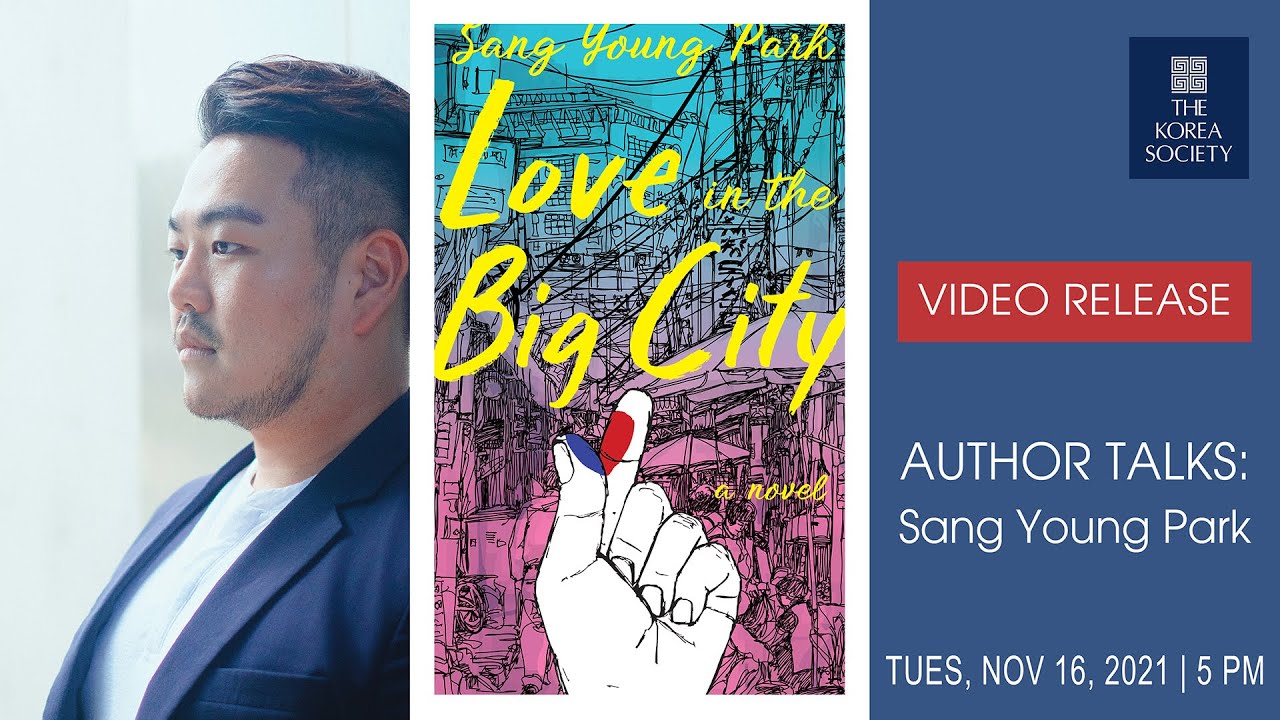

Seoul is where I spent the bulk of my twenties as a Korean American expat living with a voracious debauchery that I see captured now with startling familiarity in South Korean author Sang Young Park’s new novel Love in the Big City, which made its English language debut (translated brilliantly by Anton Hur) in mid November.

An exuberant hunger drives the characters of Love in the Big City, people who are young, broke and eager to indulge in the many pleasures of Seoul, be they carnal or culinary. “I would do anything I was told by whoever bought me a drink,” explains the book’s narrator, a gay university student named Young, in an early chapter. “I’d never refused alcohol or raw fish in my life,” he says later, describing a date with an older man who covers the bill.

Despite his meager student budget, Young is constantly asking for more from Seoul’s bounty. In one scene, a girlfriend named Jaehee catches him furiously sucking face in a parking lot with a stranger who has plied him with six shots of tequila. “Just eat him, why don’t you?,” she jokes as she stumbles across Young in this moment of unabashed zeal.

I know this appetite, and the wily calculus that goes along with it, all too well from my own youth in Seoul. I wanted a taste of the good life despite my paltry journalist’s salary (which is why I finagled my way into writing restaurant reviews where my newspaper would foot the bill). But of course, the stakes are higher for Young (and his author, for that matter) as a queer man in a society that marginalizes and carries stigmas against people like him.

“The LGBTQA+ community is not well-represented in mainstream Korean society. Koreans are not aware that we have always existed, among them and around them,” Park said in a video interview with The Korea Society when the English edition of Love in the Big City launched in November. “They think of us as characters on Netflix or a group that politically correct people advocate for. They don’t think of us as their family members, their friends and their neighbors. In this society, I am happy to be labeled as a queer writer and to be promoted and consumed as one.”

And South Korean readers have devoured Park’s work, a necessary, exciting addition to Korean literature, making him a national bestseller in his home country. There’s a generosity and biting humor that imbues his stories, with glittering descriptions that render our food-and-drink-obsessed culture in liquid-crystal high definition.

For Young and his loved ones, booze is an indulgence, but cooking stands in as the ultimate act of care. When a friend gets an abortion, Young decides to make miyeokguk, a seaweed soup, for her. It’s an emotionally meaningful dish and a dark joke, albeit one Park chooses not to explain because it’s common knowledge in Korea that new mothers often eat miyeokguk, which is rich in iodine and calcium, to replenish the body after giving birth. (Miyeokguk is also a customary birthday meal, in honor of one’s mother.) But rather than drooping into mawkish sentimentality, in Park’s hands the scene twists into sharp, black comedy, with Young deeming the dish a “total failure” and his friend calling for a cigarette instead.

My first reaction to such scenes was to cackle in delight. Despite the heavy subject matter – in addition to abortion, Park writes about HIV, a parent’s declining health, and a series of devastating heartbreaks – the book is buoyed by wit served at the hard-and-fast pace of the K-pop dance hits that Young loves so dearly. Hur, the book’s translator, manages to preserve that rhythm in English through a flawless, breezy millennial vernacular that veers artfully between slang like “dickmatized” and poetic ruminations on “the taste of the universe” within the span of a single chapter. The delicious, unbridled joy in Park’s depiction of queer Korean life is revolutionary and fun as hell to read.

But Love in the Big City’s real effect was how it intensified my yearning to return to Seoul. At a time when international travel is ill-advised or all-out barred (South Korea still requires U.S. travelers to quarantine to prevent the spread of covid-19, with some exceptions, and neighboring Japan just closed its borders to foreign visitors), I wish I could sit over a table of burbling stews with treasured old friends whom I haven’t seen since the pandemic began, revisiting all the desires and ambitions that we once craved. For now, settling into the pages of Love in the Big City feels as close as I can get.

Hannah Bae is one-half of Eat Drink Draw, a food writing-and-illustration collaboration with her husband, Adam Oelsner. She is a freelance journalist and nonfiction writer who is focused on Korea and its diasporas.